When I was a kid my father went back to school for his MBA. (For a while I thought everyone was saying “NBA,” but then I realized that he’s actually not so tall and couldn’t secretly be a professional basketball player.) Anyway, after his classes he would come home and try to explain to me what he was learning. I guess he figured that if he could explain it to a 9 year old, that meant that he knew it from top to bottom. I wasn’t bashful then about asking questions when I didn’t understand something, and I’m still not. That’s how you find the truth. Of course, at the time I didn’t think it was unusual for a kid to have an understanding of supply chain economics or financial analysis. I thought all the kids my age understood this stuff – because he made it simple. I don’t think I remember much of what he taught me at the time, but I still see the value in asking questions without worrying how they might sound.

Asking questions is one of the most important things that I do when I’m working with someone on their presentation. And I will ask a lot if you give me the time. It takes time and a certain amount of patience to get to the simple, powerful idea. Over the years of doing this, I’ve noticed that there are really three distinct types of partnerships I encounter in this kind of work, with differing levels of interest in constructing simple, powerful stories.

Type 1: Sold out for simplicity

Some people I have worked with just get it. They come to me to hash out their ideas and are open to the discussion. What’s really important here? How does this fit into our story? Are we giving them facts or telling a story? Why does this matter to your audience? Why is it relevant? I turn the fact that I don’t know as much about your subject as you do into an advantage. If you can explain it to me and I get it well enough to help you simplify it, it means that you know it pretty well, and it means we’ve found the story.

Type 2: On board, but not much time

Some people I have worked with have a basic understanding of the value of simplification and putting less on the slide, but don’t have a huge amount of time to devote to the process of really hashing the ideas out. In these cases, what we get is usually a hybrid between a simple and powerful story with a clear and beautiful visual aid, and something approaching more typical powerpoint slides. This is the middle course, and to a degree it limits the amount I can do to make the presentation be it’s most effective. But it’s a definite step in the right direction.

Type 3: Meh

And, finally, some people I’ve worked with over the years don’t, at first glance, appear to grasp the concept at all. I used to think that they didn’t really “get it” or have interest in reaching for a higher standard or a better presentation. But I’ve come to think differently about this dynamic. It’s not that they don’t get it, it’s that they don’t have the time or interest to go through the process of hashing it out. This is a very different thing.

It’s true that some people don’t initially wrap their head around the big picture, which is what a story is. They tend to focus on the granular – often they are masters of the details, which is an important skill in it’s own right. But even with people that are detail-first, rather than big-picture-first, with time and an open discussion, we can still get to the simple, powerful truths. But that’s the kicker. Time and an open discussion. A person has to be invested enough in the idea that making a presentation be audience-centric has value, and they have to believe that the beautiful and effective slides that will come as a result are worth the effort. Not everyone can say yes to these two things. And that’s ok. My inexplicable interest in presentation theory and design isn’t a passion many people share. Most people just want to get the presentation done so they can move on to the next thing. Reaching a higher standard for their presentation isn’t their highest priority. This is an understandable point of view.

This isn’t ideal presentations, it’s real world

So how do I approach the work when I’m working with type 3; when what I’m asked to do is just take the same abundant details and make them look better? I’ll usually bring up my ideas about simplification, and making it a story. Being audience-centric and not confusing the script with the visual aid. I feel there is value in talking about the theory even if it doesn’t go anywhere. But once I’ve shared my $0.02 worth, I work with the person wherever they are. There are a few things I’ll do with the inevitably busy slides that come out of this dynamic.

First, I pretty much never give up negative space, even if it means smaller fonts. For those unfamiliar with the term, negative space is the area on your page (or slide) that doesn’t have anything in it. It serves a valuable function because it makes what’s on the page easier to read, and it helps the eye know where to go.

Secondly, I’ll make my best guess about hierarchy and determine what on the page is important. If you have a lot on the page, but give everything equal weight, again, it’s hard to read. Choose what you think matters most and make it more dominant. This also means getting comfortable with smaller fonts for the stuff that’s less important.

Third, I’ll split a slide where I think it makes sense. If you’re going to cover 20 things on one slide, it will take the same amount of time to cover 10 things on one slide and 10 on the next. And it lets the content breathe a little better.

So why am I so comfortable making these kinds of decisions? Am I just being a design snob? Not at all. Believe it or not, using a smaller font and retaining a little negative space actually makes the page easier to read. The reason is functional.

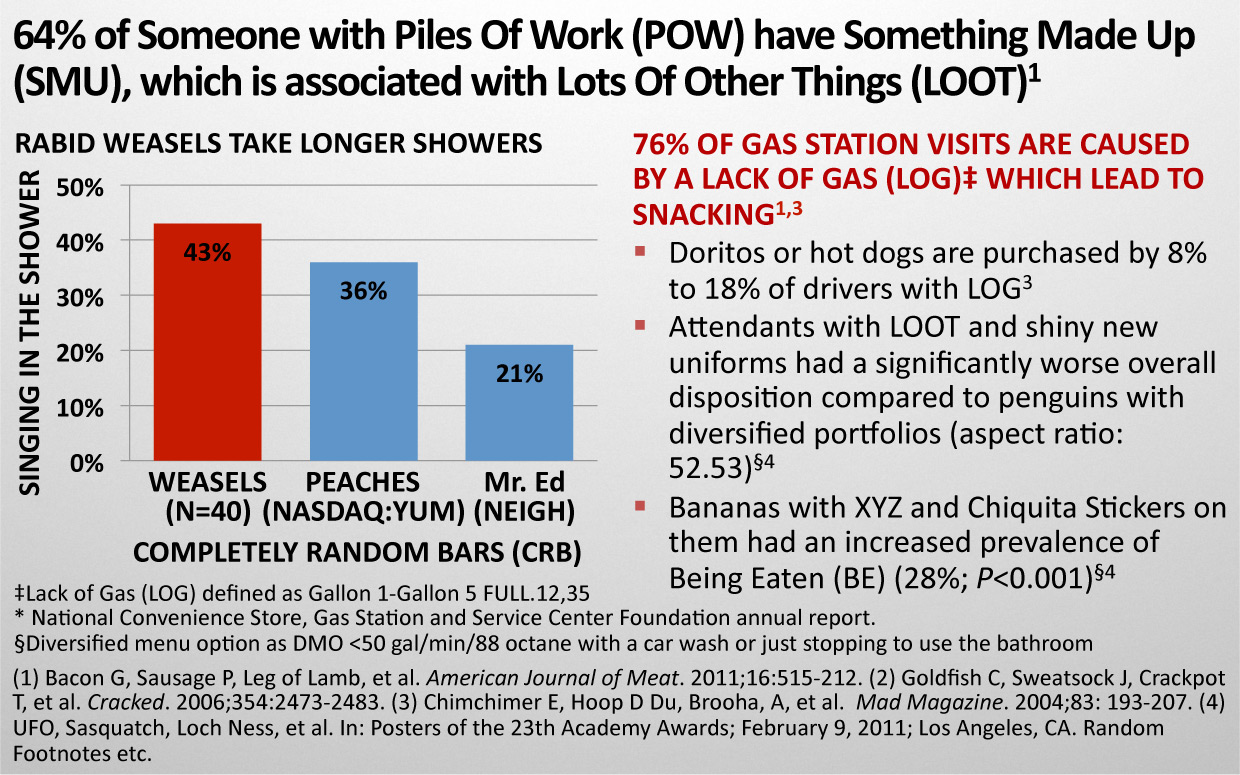

Here is a slide that has everything as large as it can be and it’s so dense you have trouble reading it. The fonts are bigger, which a lot of people think will make it easier to read. But loosing the negative space has quite the opposite effect.

Here’s the same slide (again, WAY too much information) but by making decisions about hierarchy and giving it a little room to breathe, it’s actually easier to read.

So this is a slide that, even still, tends to make me cringe just a little. But this is presentations in the real world. Not everybody has the time or inclination to work on the story. Not everybody wants to make it audience-centric. Sometimes all they want you to give them is a better-looking complicated idea. And that’s ok. I’m here to serve, and am here to do so on your terms.

The truth is, no matter how good the designer is, slides like this can’t really be made good without evaluating and simplifying the story. But that’s not what’s unfortunate about a slide like this. The unfortunate thing is the missed opportunity for dialog, partnership and human connection. The goal of any presentation is to reach people. This slide isn’t an effective tool towards that goal.

So I’m here for any kind of partnership people need. The quality of the work that can be produced is largely determined by the nature of the partnership we enjoy. Being able to present a simple, powerful story is a valuable career skill, and one I love to help people develop. It’s not difficult, but it does require adequate time. Most people that give it a shot find it to be worth it. Talk to me if you’d like to work on your story together. I’ll ask a lot of questions, but if it makes sense to me, it’ll make sense to anyone.